World Update: Egypt’s inflation falls behind Nigeria’s as bold reforms pay off

Nigeria Update: 12 firms ‘harvest’ N268.7b from rights issue

June 19, 2018

Nigeria Update: Nigeria, Germany explore new opportunities to strengthen economic ties

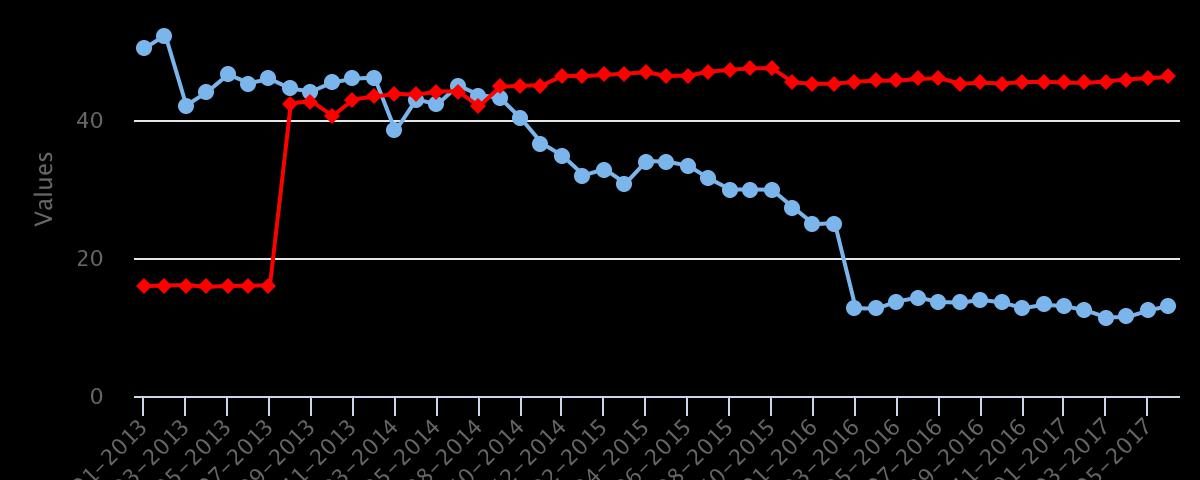

June 22, 2018Annual inflation in Egypt has fallen behind Nigeria’s for the first time since a raft of painful reforms from a currency float to fuel subsidy cuts that started in 2016.

While North Africa’s largest economy has undertaken tough policy choices, Nigeria has struggled to take definitive action. The annual inflation rate in urban parts of Egypt in May rose at its slowest pace in more than two years to 11.4 percent, a considerable way off the 30 percent mark it crossed in 2017 and 20 basis points below Nigeria’s 11.6 percent annual inflation for the same period.

When Cairo followed up its floatation of the Egyptian pound by raising taxes almost immediately, it sparked runaway inflation, the very problem the Nigerian monetary authorities were trying to avoid when the central bank kept the naira pegged to the dollar at the official window.

“The lesson to be learnt here for Nigeria is the need to take a long-term approach to implementing reforms rather than always applying short fixes,” one government source with knowledge of the matter said on condition of anonymity.

The source however admits that the political cost of non-populist reforms like an upward review in electricity tariffs and petrol prices make it difficult for the government. There was little opposition in Egypt when the currency was devalued, because they practice a dictatorial system of government, the source said. “So it’s not entirely the same as Nigeria, but that is no excuse for government to drag on reforms.”

Meanwhile, the spread between Egypt’s official and parallel market rates have collapsed to 17.8 EGP per dollar, since the float last year. In Nigeria, the spread between the official and black market-one of several other markets- has remained at N57 per dollar (N306 vs 363).

With a year to the general elections, Nigeria may have to wait for any Egypt-type economic reforms, analysts say. There as little expectations that an unsustainable N145 per litre retail petrol price would make way until after the elections.

“This administration missed the best chance to ring in those reforms,” one business leader told Business Day.

“Most of the reforms should have kick-started in the first year of administration.”

While the government is not entirely idling away- given that it has implemented tax reforms like the Voluntary Assets and Declaration Scheme and some ease of business reforms which earned it a jump in the World Bank ease of business index to 145 from 169, the feeling is much more could have been done.

Egypt’s Minister of Electricity Mohamed Shaker announced new electricity prices for businesses and consumers, which will see costs rise 25 percent for households and 42 percent for industrial use starting next month.

Slashing subsidies comes as part of Egypt’s economic reform program, which include cutting subsidies and imposing new taxes. It is also part of a three-year $12 billion International Monetary Fund (IMF) loan agreement, which Egypt clinched in 2016.

Electricity prices went up last year, with price increases ranging between 15-36 percent depending on the consumption bracket.

Phasing out subsidies will continue to take place every year until they are completely eliminated by the end of fiscal year 2021/22. The new prices will take effect in July.

“Both Egypt and Nigeria have fuel subsidies. Both countries also need to increase their investment to GDP ratio, which is 15% of GDP or less in Egypt and Nigeria,” Charles Robertson, chief economist at Moscow-based investment bank, Renaissance Capital, said in an emailed response to Business Day.

“It needs to be 25% of GDP. Egypt is cutting its fuel subsidy so that it can spend more on investment. This will help Egypt in the long-term. Nigeria will struggle to increase government investment when so much money is spent on the fuel subsidy,” Robertson added.

Not only is inflation trending downwards in Egypt, other gains from its painful but promising reforms are gradually sprouting, especially in foreign investment inflows.

Egypt emerged Africa’s most preferred investment destination in 2017 after recording inflows worth $7.4 billion, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

UNCTAD said Egypt’s investment attraction was as a result of “wide-ranging economic reforms such as financial liberalisation, which fostered more reinvestment of domestic earnings.”

Egypt’s FDI was more than seven times the inflows Nigeria mustered- in 2017- $981.75 million, according to the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS).

Egypt introduced a new law for the setting up of a natural gas regulatory authority charged with licensing and devising a plan to open the gas market to competition,” the report said.

“Egypt promulgated the Industrial Permits Act and its executive regulations, aiming to ease procedures for obtaining licenses for industrial establishments,” the report said.

“The country also put into effect a new investment law, aiming to promote domestic and foreign investment by offering further incentives, reducing bureaucracy and simplifying administrative processes,” the report added.

The report also noted that Egypt issued a decree establishing the “Golden Triangle Economic Zone” as part of ongoing efforts for investment facilitation and promotion.

The Nigerian Central Bank pointed to Egypt’s inflation crisis as an example of how a currency float could go bad, and dug in with currency controls and resorted to creating several foreign exchange markets while holding on to a subsidised dollar exchange rate.

The CBN’s move to create other fx markets has largely skewed to the success of the Investor and Exporters window, which was has been a revelation since its launch in April 2017. Over $30 billion has been traded at the I & E window, as it has helped lure back portfolio investors who fled in the thick of capital controls in 2016.

While Nigeria swiftly dodged the more painful route of floating the naira, the government hasn’t had much success with petrol prices.

Crude oil prices have held over $70 per barrel in the past month and while that seems a boon for Africa’s largest oil-producer’s finances, it is actually a headache for petrol prices.

The current petrol price template introduced in Nigeria on May 11 2016, after acute fuel shortages crimped economic output and fanned inflation, saw prices jump 62 percent to N145 per litre from N86.50 per litre, as officials ran out of ideas on how to sustain artificially low prices at a time of falling revenue.

However the current oil price and exchange rate have rendered the price obsolete, given that oil sold for $45 per barrel at the time of agreement on the price peg and the exchange rate was N280 per US dollar.

The naira has exchanged for N305 per dollar at the CBN window since 2017, while the interbank rate and black market rate is much weaker at N320 and N360 per dollar.

There have been bouts of special intervention for petrol marketers who get dollars at subsidised rates since the last price review and the worry for analysts has always been that it can only stand as a short term fix, as it is unsustainable in the long run.

“So even Saudis are now paying 54 US cents for a litre of fuel. Nigeria’s subsidised price of NGN145 is equivalent to 40 US cents per litre. Yet Saudi produces 5 times more oil than Nigeria and exports 27 times more per person,” Charles Roberston, the chief global economist at Russia-based investment bank, Renaissance Capital said in a tweet.

“Populists are wrong to suggest that Nigeria should keep petrol prices low just because other energy exporters do so. These other countries export far more energy per capita and are far wealthier, and can therefore better afford petrol subsidies,” added Robertson.

Saudi Arabia, the world’s biggest oil exporter and the largest economy in the Arab region, froze major building projects, cut cabinet ministers’ salaries and imposed a wage freeze on civil servants to cope with 2016’s budget deficit of $97 billion. It also made unprecedented cuts to fuel and utilities subsidies. It aims to balance its budget by 2020.

Abayomi Fawehinmi, an energy analyst said, “Unlike Saudi Arabia that practices a monarch system of government were the crown prince is not looking for votes, In Nigeria the scenario is different, because election is next year so the government will not want to take a decision that will attract public outcry.”

“We lost our chance to remove fuel subsidy when the price of oil crashed in 2015, then it could have being understandable but not now as the misery index such as inflation and unemployment keeps going high,” Fawehinmi said by phone.