Article Update: Hard Work in 5 Easy Steps: Understanding Perseverance in the Modern Age

Article Update: What Should You Keep?

August 18, 2017

Article Update: Entrepreneurs Need More than Funding. They Need a Community.

August 18, 2017Work hard and you can achieve anything. That’s a bit of advice that’s been repeated to us so many times that it’s sort of lost its meaning. The problem is that we already feel like we are working hard, but for many of us, it seems like we aren’t getting anywhere.

So, is that advice complete bunk?

I would argue that it isn’t. Rather, I think what’s gone awry is our definition of hard work.

The thing about trying to nail down a definition of hard work is that, as I mentioned, most of us already believe we are hard workers. We went to college. We got good grades. We got jobs. We did exactly what our fathers and high school guidance counselors told us to do. We get out of bed, we go to work, we pay our bills, we keep ourselves and our homes neat and tidy, and we go to bed each night feeling somewhat exhausted.

But the problem with that conception of hard work is that it’s not what all those successful people meant when they gave you the advice “work hard and you can achieve anything.” Most of what we do on a day-to-day basis is simply what we have to do to survive. Your job, your chores, your obligations to your family and the favors to your friends—that’s not hard work. That’s regular work. That’s your routine—the stuff that you and every other human being does every single day.

Hard work is what you do on top of all that. It’s what you do after you’ve put in your eight hours, after you’ve cleaned your apartment, after you’ve kept all your appointments and followed through on all your promises. Hard work is above and beyond—and it’s the only thing that will push you above and beyond.

That’s not even the end of the story. What makes hard work truly hard isn’t even the work itself. It’s everything else that you take on when you make the decision to work hard toward your goals. It’s the brutally honest self-evaluation, the tough personal sacrifices and the ever-lurking uncertainty.

That’s what we’ll be discussing among the five “easy” steps to hard work. As you’ll discover, this article title is more than a little tongue-in-cheek. The easy part of these steps is learning them. The hard part is doing them. Let’s get started.

Overview: The Five Elements of Hard Work

Hard work is but one of the ways you can achieve your goals. For those of us who aren’t inordinately wealty, smart or Lucky, it’s the only way. While each person’s path to success will be unique, the anatomy of the hard work that they do often looks very similar. For most successful people, the hard work that they put forth included all of the following:

- The Drive – This is the motivation, the inspiration, the entire reason you work hard. This is the engine that pushes your efforts forward.

- The Plan – If The Drive is the heart of your hard work, then the plan is the skeleton. The plan maps out your course of action and helps plot your progress and keep you on track.

- The Grind – The Grind is the point when working hard stops being fun and exciting and starts becoming tedious, stressful and perhaps even discouraging. How you handle the grind is often what separates the winners from the quitters.

- The Sacrifice – This is the crux of hard work, and the one thing that makes hard work truly hard. Any ambitious goal requires significant personal sacrifice. Enduring the strain in your relationships, finances and comfort level is the real test.

- The Payoff – This is the brass ring. In order for hard work to be worthwhile, you have to define a number of goals and milestones and recognize when you’ve achieved them. And once you do, you have to up the ante and keep going.

Let’s look at each one of these one by one.

The Drive – Find Your Motivation

When considering hard work, a good question to ask is: “Why?” Why bother getting up before dawn to train? Why bother working two or three jobs at once while simultaneously attending night school? Why bother scrimping and saving and forgoing earthly pleasures in order to pour every spare cent into your venture? The answer: motivation.

Motivation is what sets hard work in motion. Motivation is what keeps us productive in spite of the grueling grind and the tough sacrifices. But just as there are sustainable sources of energy as well as unsustainable sources of energy, there is negative motivation and positive motivation. Both will bring you success. But one is obviously better than the other.

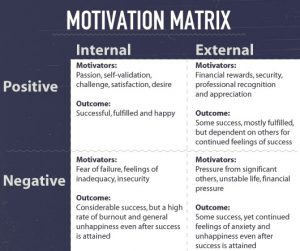

The Motivation Matrix: Positive vs. Negative Motivation

Writing for PsychologyDay, Dr. Jim Taylor defines motivation as “being able to work hard in the face of obstacles, boredom, fatigue, stress, and the desire to do other things.” Each person has a different motivation that drives them toward success. Dr. Taylor illustrates this with the motivation matrix, which breaks down motivation along two dimensions: external vs. internal and negative vs. positive. Each combination—internal-positive, external-positive, internal-negative and external-negative—can provide sufficient motivation to net you success. But the experience and outcome of that journey to success can be very different.

The ideal type of motivation is internal-positive. This, according to Dr. Taylor, is when “the motivation is coming from a place of strength and comfort.” This is in contrast to being driven by something like insecurity (internal-negative) or a need for attention (external-negative). Studies show that these negative motivations are not uncommon, especially in business settings. This negative motivation, after all, is an archetypal role in many movies: the driven, successful businessperson who achieves his or her goals but doesn’t feel fulfilled because he or she was motivated by the wrong reasons. The turning point in these narratives is when the protagonist chooses to walk away from the success and pursue happiness (and perhaps success) elsewhere. But in the real world, making this leap isn’t always so easy.

Success vs. Happiness: A Rags-to-Riches Story

For example, take the real life story of Aimee Elizabeth. From the age of 15, Aimee was broke and homeless, working many low-paying (but legal) jobs to keep from starving to death. By the time she was 18, she did manage to get a foothold on her savings, thanks to a policy typist job she got at an insurance agency. However, after the insurance agency changed ownership, there were a number of changes to the company’s structure, including a new dress code policy.

“They expected me to conform,” Aimee tells Primer. “I was outraged. I didn’t want to spend my hard earned money on clothes I would never wear except at work. I had about $5,000 saved in the bank by this time, so my common sense was over-ridden by my youth, and I quit.”

Looking back, there were probably other reasons why Aimee felt driven to leave the highest paying job she had ever had. “I realized that I could never earn what I believed I was worth by working for others,” she says.

So, by the time she was 20, she started her first successful business. It thrived for nine years. Her personal life, however, did not. When she was an abandoned, hungry and homeless teenager, she had made a vow to herself never to have children for fear that they might end up like she was when she was 15. That decision, along with her drive for success, made it difficult for her to maintain romantic relationships.

“Even though I was now financially sound, I just could never ever get over that visceral fear of being homeless and hungry again. I couldn’t ever make enough money to get past the fear I had of innocent children depending on me. So I not only missed out on the joys of motherhood, I missed out on some really terrific guys because of this lifestyle choice,” Aimee says.

Aimee went on to build and sell four businesses, allowing her to retire when she was 38 years old. By age 49, she was a multi-millionaire, successful real estate investor, guest speaker, business consultant and a bestselling author. But she was, and is to this day, alone.

In the beginning, Aimee was driven very much by external-negative motivation. She worked to escape poverty. Ironically, that same drive continued to carry her even after the threat of becoming homeless and hungry again faded. At that point, her motivation transitioned from external-negative to internal-negative. The fear of destitution was no longer part of her circumstances—it was something deeply ingrained in her. She couldn’t shake it. In spite of her success, Aimee says she regrets not going into therapy in her 20s in order to overcome these feelings. Unfortunately, she never made that transition to a positive-internal motivation.

“I will forever be that homeless and hungry fifteen year old girl on the inside,” she says. “Being on my own so young taught me to only depend on myself, and now 30 plus years later, it’s a habit I doubt I can break. I overcame my homelessness and hunger. I sometimes regret my personal choices because of so many years I have spent alone. And now at my age, I wonder if I will always be alone. Will I grow old alone and die alone too? It seems likely. And so rather than dwell on it, I just continue to make more money, to distract myself from the loneliness.”

As Aimee’s story illustrates, success can be realized even through negative motivation. But happiness and success don’t always go hand-in-hand.

Doing the Hard Work: The Drive

Taking the time to evaluate your motivation is already somewhat above and beyond the routine. But it becomes truly hard work when you muster up the time, focus and courage to do a brutally honest inventory of what’s driving you. For extreme cases like Aimee’s, you may need to seek help from a third party in order to tease out the true nature of your drive. This can be a professional therapist or a mentor or a trusted friend. For the rest of us, it means taking a serious look at the direction of your life and challenging your assumptions about your goals. This can be difficult. If you’ve spent your childhood, your college years and a few years on the job market believing you’d be a pro basketball player or a radio broadcaster or a brain surgeon, entertaining the notion that you might not really want these things can be downright painful. Maybe you’ll let down your parents or coach or teacher who always believed in you. Or maybe your aspirations to be X have always defined a big part of your identity. Whatever the case, if your heart isn’t in it, it will only get worse as you get further down that path.

Take the time now. Do the hard work. Find out what really motivates you and make sure it aligns with what will make you truly happy.

The Plan – Map It or Scrap It

Another Primer article, Map It or Scrap It! The Real Secret To Success, succinctly lays out the case for plotting out the actual steps that it will take you to achieve your goals. When it comes to doing actual hard work, that element becomes even more important. There are many reasons for this, but chief among them are (1) the need to break the hard work down into actionable steps and (2) the need to enroll all stakeholders in your venture.

When you think about your big goals, you tend to think of them in terms of a lifetime. But when you do hard work, you go day by day. Establishing a plan lets you take the big goal of “What do I want to do with my life?” and break it down into “What do I need to do over the next five years?” and then “What do I need to do this year?” and then “What do I need to do this week?” and then “What do I need to do today?” and then finally “What do I need to do right now?”

This lowest level of granularity is the important one, because it’s the one where you’re going to meet the most resistance, both internally and externally. Internally, you’re going to meet resistance whenever you get into The Grind. Whenever you find yourself working through the night or the weekend instead of sleeping or lounging on the couch or drinking with friends, you’re going to ask yourself “Why am I doing this?” The Plan helps you overcome these feelings. It helps you take the action you are doing right now and connect it to that big goal, even when it makes the present moment incredibly unpleasant.

The external resistance you’ll encounter during your daily toil is trickier. As a society, we tend to glorify the notion of hard work. But we tend to do so in retrospect after the hard work has already paid off. Plus, we tend to glorify hard work from a distance—it’s the award presenter or obituary writer who lavishes praise on the hard working attitude of the recipient or subject.

When you get down to the personal level and the present moment, our feelings toward hard work become more ambivalent. With The Payoff still somewhere in the distant and uncertain future, it becomes easy to feel resentful towards hard work and the people who choose to do it (you). This will be explained further when we talk about The Sacrifice, but the result is that when the going gets tough (which it will), you will need to make the case that all this struggle and sacrifice is worth something. This is where The Plan comes in.

The Plan becomes an important “marketing” tool for explaining why you are making the choices you make on a day-to-day basis. It gives you a framework for all the thousands of times you’ll have to choose between doing A or B. Not only that, it gives everyone in your life an opportunity to either object to or buy-in to The Plan. It gives your girlfriend or business partner or whoever else relies on you a chance to run for the hills before getting dragged into your taxing, sleep-deprived, frustrating lifestyle of hard work.

Aimee Elizabeth, the rags-to-riches entrepreneur from the previous section, has admittedly had troubles finding a significant other who is comfortable with her plan. But because she is upfront about her ambitions, it prevents her from becoming entangled with someone who is going to bail on her down the road, or worse, sabotage her for the sake of their relationship.

“My fondest wish would be to find a man who can accept me as I am, and love me to death anyway,” Aimee told Primer. For better or worse, Aimee hasn’t compromised her ambition for the sake of a relationship. But when she does find that person who accepts her—ambition and all—then she’ll have a partner in her ongoing ventures, and not a naysayer or rival.

In conclusion, this section isn’t about making a plan. It’s about having one and making sure all the stakeholders agree to it, or are at least aware of it. In the narrative of your success, The Plan is the founding document. Although not everything will go exactly according to The Plan, all actions, milestones, setbacks and decisions will harken back to The Plan. This is how you will contextualize the efforts and sacrifice you will put into achieving your goals. And this is how you will measure the hundreds of little successes and failures along the way to the big payoff.

Doing the Hard Work – The Plan

Making a plan is like declaring a major. It’s something that many of us shy away of because once The Plan has been laid, we are accountable. When The Plan comes into form, it highlights the ways in which we are delinquent and it maps out the hard road we have ahead of us. This can be incredibly daunting.

Advertising The Plan to people who are close to you can also complicate your routine life. For many people, The Plan becomes an ultimatum. If you say, “I’m devoting the next 10 years of my life to developing a rural commune of organic farmers,” and your significant other was thinking in the back of her mind, “I’d better be back in the suburbs and pregnant in the next four years or I’m wasting my time,” then there’s going to be some strife.

But without The Plan, your work amounts to nothing but treading water. Do the hard work. Pick a direction. And start swimming.

The Grind – Don’t Ease Up, Don’t Give Up

When you were graduating from high school, someone older probably sat you down and gave you a certain piece of advice. Maybe this person was a father or an uncle or a family friend, but whoever he was, he had been in the workforce for a while and wanted to pass a bit of wisdom to you. Here’s what he said:

“Choose a job that that you love, and you will never have to work a day in your life.”

That tidbit of advice, while well-meaning, is, sadly, a crock of romantic wishful thinking. No one—not even Oprah—lives this supposed axiom. Even if you are a freelance work-at-home marine biologist/rock star/wizard, there will be times when you just do not want to get out of bed and do your job. This can be a simple case of the Mondays. Or it can be seven consecutive years of thankless toil before you see a single cent of profit. But it is a fact of life.

Dr. Jim Taylor, writing for Psychology Today, calls this “The Grind.” The Grind is when you are doing work that takes “you far beyond the point at which it is fun and exciting.” The Grind is stressful, tiring and tedious. It also happens to be the point where it really, really counts.

As Dr. Taylor puts it: “Many businesspeople when they reach this point either ease up or give up because it’s just too darned hard. But truly motivated businesspeople reach The Grind and keep on going.”

To beat The Grind, he recommends striking a balance somewhere in the middle of the love-hate continuum. Managing to truly love The Grind—the paper pushing, the boring meetings, the bleary-eyed mornings when you punch the clock at your 9-to-5 job after pulling an all-nighter on your side project—rarely ever happens. On the other hand, openly hating The Grind is a recipe for burnout. That’s why Dr. Taylor writes: “I suggest that you neither love nor hate The Grind; you simply accept it as part of the deal in striving toward success.”

In Psychology Today, Dr. Taylor was writing about success in the business world. But it applies outside the cube walls as well. Let’s take a look at another real life example.

Grinding Across the Polar Ice Caps

As a newlywed, Akshay Nanav took a big risk. Just four months after his wedding, the 27 year old ex-Marine walked away from his full time job, plunked down $15,000 and embarked on an expedition to ski across the Greenland ice sheet, the second largest ice cap in the world. To do this, Akshay had to spend nearly every cent of his savings, leave his family behind and spend a month dragging a 195 pound sled across 350 miles of unforgiving frozen landscape.

In embarking on this journey, Akshay was very much realizing part of his dream. The Greenland ice sheet was a proving ground for Akshay. He had been training for the trip for three years, and conquering the ice cap was a milestone toward his next goal: traversing the Patagonian Ice Sheet and then, in the future, the North Pole. Despite being positively motived to undertake this challenge, the nature of the endeavor guaranteed moments of pure grind.

“There were most definitely points in the journey when I did not want to be there, when I was miserable and just wanted to go back home to the warmth and comfort of my bed, my wife, my hot shower, sitting on a couch, all of those luxuries,” Akshay tells Primer. “During those moments of misery, there was really no choice but to continue on. The only way off the icecap was across, so I just worked on changing what I was focusing on.”

Because of Akshay’s drive and plan, he was able to make this conscious choice to readjust his focus.

“For me, drive is about staying focused on the future and working backwards from there. I do not work from now to the future. I work from the future to the now. By doing so, all the struggles and sacrifices become worth it, because the future vision lives within me every day,” he explains.

“If and when doubt shows up, I look at the pain-pleasure dynamic of the decision I am making,” says Akshay. “What is the pain that will result if I don’t continue down this path? What is the pleasure if I do? Generally, the thought of pain kills doubt and the pleasure empowers me to continue onward.”

To Akshay, the pain of giving up on his journey across the ice cap would have meant delaying or possibly ending his dream of “reaching the poles, exploring the harshest continents on the plant and discovering the infinite capacity of the human spirit.” Back at home, the pain of giving up on his own business would have meant working for someone else for a paycheck instead of being his own boss. “The need to avoid that pain and the desire to gain the immense pleasure from making those sacrifices reinforces my decision and I continue forward as boldly (or stupidly, some would say) as possible,” he says.

In many ways, Akshay’s grind can represent our own. Opportunities, like the polar ice caps, are out there—but for each year we hesitate, allowing ourselves to grow older and more complacent, they diminish, slowly softening and melting away. Making the choice to follow your passion and stick to your plan will inevitably wind you up in the middle of your own ice cap—exhausted, discouraged and wanting to quit. How you decide to act in that moment is every bit as crucial as the decision you made at the beginning of the journey.

Doing the Hard Work – The Grind

Even though you may feel like a latent rock star or an underappreciated genius, there will be times when you are low, humble and just plain bored. There will be times when everything seems like bullshit and nothing makes sense. There will be times when The Plan seems like a pipe dream and The Drive seems like a drunken hallucination. Recognizing these moments for what they are and persevering through them is a major part of hard work. The Grind can happen all at once at the end of the year or once every Wednesday for the next 10 years. But in the end, it doesn’t matter when you quit. If you quit after five years of effort, the net result is the same as if you gave up two hours after you started: you gave up on your dreams. Do the hard work. Don’t. Ever. Quit.

The Sacrifice – An Unpopular Leap of Faith

I’d like to present something called the Liz Lemon Fallacy. Liz Lemon, played by Tina Fey, is the lead role in the sitcom 30 Rock. One of the ongoing jokes about her character is that she always thought that she was getting one step closer to “having it all”: a good career, the respect of her coworkers, a stable relationship and the satisfaction of knowing that she stuck to her values and stood up for what she believed in. The joke part of that is that, as nearly every episode proves, she is dead wrong. If you ever feel the same way Liz Lemon does, then you’re dead wrong, too.

The Liz Lemon Fallacy is the mistaken belief that, if you can just get yourself organized, if you can just get the hang of this certain system, or if you can just get caught up over the weekend, then you can get all your work done, stay in touch with all your friends, keep all your dishes clean, stay in shape, catch all your favorite TV shows and still have time to call your mom maybe once a week. That, as it turns out, is simply not true.

There are exactly 24 hours in each day and exactly seven days in each week. There is exactly one of you, and that body that your brain rides around in needs roughly four to six hours of sleep every night in order to function. Meanwhile, it takes about 10,000 hours of practice to become an expert at something which was cited throughout Malcolm Gladwell’s book Outliers: The Book of Success. It takes about 120 semester hours to earn a bachelor’s degree, which amounts to about 1,800 hours sitting in a class room. It takes about 40 hours to earn a master’s degree, which amounts to about 600 hours in class (and that doesn’t include time spent reading, studying and writing a thesis). These are just the things that you can easily quantify. How many hours did it take to develop Facebook? How many hours did it take to for Tesla to invent and develop the AC motor? How many hours has Michael Phelps spent in the pool?

No matter how hard you fudge the math, it’s clear that you’re not going to be able to “have it all” by waking up 30 minutes earlier or brushing your teeth in the shower or fashioning yourself a Hipster PDA. This means that if you are going to be serious about sticking to The Plan and achieving your goals, then you’re going to have to make some major personal sacrifices.

Making sacrifices, I would argue, is the hardest part of hard work. It’s harder even than the work itself. When we think about our goals and the work that we’ll have to put into them, we tend to downplay this part of the equation in our mind. For example, if you are imagining yourself pursuing a career as a novelist, it’s easy to imagine typing long into the night. “All I have to do is write and write and write, right?” you think. “No problem. I love writing. Otherwise I wouldn’t want to be a writer.”

But that’s not the hard part. Sacrifice isn’t about what you do to reach your goals; it’s about what you choose not to do for the sake of your ambition.

This is worse than it sounds. In order to stick to The Plan, the things you have to give up will be so important to you that it hurts to see them go. This is the definition of sacrifice: the act of surrendering something of value for the sake of a greater purpose. You don’t read about biblical figures sacrificing pigs or sickly runts. They killed the fatted calf.

Likewise, the sacrifice you make for the sake of your goals will have to be something near and dear to you. It’s easy to be caught off guard by this. Part of the reason for that is that, like hard work in general, making sacrifice is something that we tend to feel we are already doing. Specifically, we as a society like to pretend that we are making a sacrifice by giving up material possessions. Before we forge The Plan and come face-to-face with The Grind, we factor this runty sacrifice into our mental bargaining. “It’ll be no problem to start my own business. I can live off ramen noodles and drive my beater of a car for a few more years to make ends meet. I don’t need material things to make me happy,” we think.

But things don’t always work out so easily. Eschewing a life of conspicuous consumption and lavish luxuries isn’t some kind of righteous, enlightened path. It’s how pretty much everyone already lives. As much as we complain that we live in a materialistic society, no one really believes that owning a Jaguar or a designer watch is their life’s purpose. Most of us place far more value on experiences, relationships and security. These are the things that make us truly happy. And these are the things that you’ll have to sacrifice for the sake of hard work.

The Plan occupies an immense amount of space in your life. For many, it consumes it entirely. Giving 110 percent to one cause means that you have less than zero percent to give elsewhere. Your other plans will have to be cancelled or put on hold. Your relationships will be tested and will likely terminate. You will miss funerals, reunions, bachelor parties, holidays, movie premieres and so much more. You’ll uproot yourself from the place that you call home and move to the place where your dreams have a better chance of taking root, leaving your friends, your family, your girlfriend and your comfort zone behind. Perhaps even more painfully, you’ll have to give up on some of your other dreams that aren’t directly related to the one you are pursuing in The Plan. (You can’t be an astronaut and a rock star—at least not to my knowledge. If I’m wrong, please post a link to the exception in the comments.)

Because you are doing hard work, it means you’ll be saying “no” over and over and over again. You’ll say “no” when the people you love want you to say “yes,” and a part of you desperately wants to say “yes,” too. You’ll let go of so many things that you’ve been wanting to do, been meaning to do, or thought you had to do in order to feel alive. You’ll do these things and no one—not even you—will know for sure if the sacrifice you are making is worth it.

Taking that leap of faith and making that sacrifice is the hardest part of The Plan. But you will have to do it sooner or later. You may even have to do it more than once.

Doing the Hard Work – The Sacrifice

If you’re not making a true personal sacrifice, then you’re not working hard. You’re coasting. Can you coast your way to success? Yes. If you are rich enough, lucky enough or talented enough, you certainly can achieve your goals without making any personal sacrifice. But that typically means that you’re simply setting the bar too low. This translates into barely any achievement at all.

The struggle between you and the obstacles to your goals is a war of attrition. There is no limit to what you can put forth. You only admit defeat when you refuse to make any further sacrifices.

Do the hard work. Give up something you love or give up your dreams. You can’t have it all.

The Payoff

Although the previous four sections might seem discouraging, that’s not the point of this article. I’m not trying to talk you out of working hard toward your goals by telling you that you’ll lose sleep, lose friends and remain forever alone. What I’m trying to convince you is that no matter how hard you think you are working, you can work harder. But in order to do so, you’re going to have to do just as much emotional and spiritual hard work as physical and mental hard work. True hard work has a disruptive effect on your life, which is exactly the intended effect. There are positives and negatives to this disruption, but if the goal that you have your sights on is truly what you want, then it will all be worth it.

In Aimee Elizabeth’s rags-to-riches story, there was certainly payoff and sacrifice. She went from being broke and homeless to being a retiree before the age of 40 and a multimillionaire before the age of 50. The sacrifice she made in doing so was the decision to harden a part of her heart at a young age, and to this day, she struggles to soften it once again. Whether this was a good bargain or not remains to be seen, but her extraordinary story proves that upward mobility is possible.

In Akshay Nanavati’s story, the sacrifice and payoff are still somewhat fresh. As of the time of this article, it’s only been three months since he walked away from his fulltime job in order to dedicate himself fully to his exploration and entrepreneurship. But already, he’s realized a number of significant milestones in his journey. The experience of traversing the Greenland ice cap was a month long payoff in itself, but it also helped him grow spiritually and physically. He now lives life on his own terms and is his own boss. He’s validated his wife’s support of both him and his ambitions. Although there is still tension, he’s reached an understanding with her. “She wants me to live the life I want and be the person that I am, just as I want her to do the same and we support each other on the journey,” Akshay explains.

What’s important to remember about The Payoff is that it’s never terminal. While it’s crucial to recognize the moments when you’ve reached a milestone or conquered a certain leg of your journey, your hard work is never truly over. Hard work is a lifestyle that you will live until you die. Take the payoffs, celebrate them, and then reinvest them into the next challenge ahead.